Introduction to Containers

- Take advantage of the native virtualization features available in the Linux kernel.

- Each container typically encapsulates one self-contained application that includes all dependencies such as library files, configuration files, software binaries, and services.

Traditional server/ application deployment:

- Applications may have conflicting requirements in terms of shared library files, package dependencies, and software versioning.

- Patching or updating the operating system may result in breaking an application functionality.

- Developers perform an analysis on their current deployments before they decide whether to collocate a new application with an existing one or to go with a new server without taking the risk of breaking the current operation.

Container Model:

-

Developers can now package their application alongside dependencies, shared library files, environment variables, and other specifics in a single image file and use that file to run the application in a unique, isolated “environment” called container.

-

A container is essentially a set of processes that runs in complete seclusion on a Linux system.

-

A single Linux system running on bare metal hardware or in a virtual machine may have tens or hundreds of containers running at a time.

-

The underlying hardware may be located either on the ground or in the cloud.

-

Each container is treated as a complete whole, which can be tagged, started, stopped, restarted, or even transported to another server without impacting other running containers.

-

Any conflicts that may exist among applications, within application components, or with the operating system can be evaded.

-

Applications encapsulated to run inside containers are called containerized applications.

-

Containerization is a growing trend for architecting and deploying applications, application components, and databases in real world environments.

Containers and the Linux Features

- Container technology employs some of the core features available in the Linux kernel.

- These features include:

- control groups

- namespaces

- seccomp (secure computing mode)

- SELinux

Control Groups (cgroups)

- Split processes into groups to set limits on their consumption of compute resources—CPU, memory, disk, and network I/O.

- These restrictions result in controlling individual processes from over utilizing available resources.

Namespaces

- Restrict the ability of process groups from seeing or accessing system resources—PIDs, network interfaces, mount points, hostname, etc.

- Creates a layer of isolation between process groups and the rest of the system.

- Guarantees a secure, performant, and stable environment for containerized applications as well as the host operating system.

Secure Computing Mode (seccomp) and SELinux

- Impose security constraints thereby protecting processes from one another and the host operating system from running processes.

- Container technology employs these characteristics to run processes isolated in a highly secure environment with full control over what they can or cannot do.

Benefits of Using Containers

Isolation

- Containers are not affected due to changes in the host operating system or in other hosted or containerized applications, as they run fully isolated from the rest of the environment.

Loose Coupling

- Containerized applications are loosely coupled with the underlying operating system due to their self-containment and minimal level of dependency.

Maintenance Independence

- Maintenance is performed independently on individual containers.

Less Overhead

- Containers require fewer system resources than do bare metal and virtual servers.

Transition Time

- Containers require a few seconds to start and stop.

Transition Independence

- Transitioning from one state to another (start or stop) is independent of other containers, and it does not affect or require a restart of any underlying host operating system service.

Portability

- Containers can be migrated to other servers without modifications to the contained applications.

- Target servers may be bare metal or virtual and located on-premises or in the cloud.

Reusability

- The same container image can be used to run identical containers in development, test, preproduction, and production environments.

- There is no need to rebuild the image.

Rapidity

- The container technology allows for accelerated application development, testing, deployment, patching, and scaling.

- There is no need for an exhaustive testing.

Version Control

- Container images can be version-controlled, which gives users the flexibility in choosing the right version to run a container.

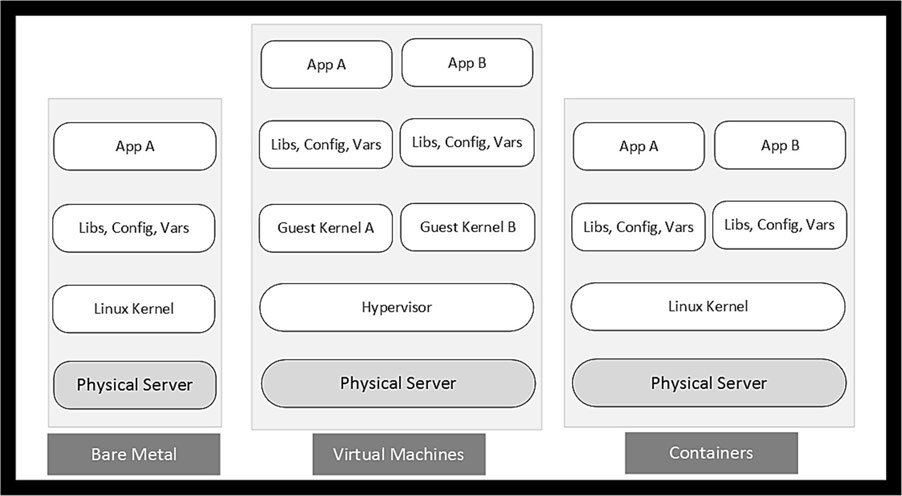

Container Home: Bare Metal or Virtual Machine

Containers

- run directly on the underlying operating system whether it be running on a bare metal server or in a virtual machine.

- Share hardware and operating system resources securely among themselves.

- Containerized applications stay lightweight and isolated, and run in parallel.

- Share the same Linux kernel and require far fewer hardware resources than do virtual machines, which contributes to their speedy start and stop.

- Given the presence of an extra layer of hypervisor services, it may be more beneficial and economical to run containers directly on non-virtualized physical servers.

Container Images and Container Registries

- Launching a container requires a pre-packaged image to be available.

container image

-

Essentially a static file that is built with all necessary components (application binaries, library files, configuration settings, environment variables, static data files, etc.)

-

Required by an application to run smoothly, securely, and independently.

-

RHEL follows the open container initiative (OCI) to allow users to build images based on industry standard specifications that define the image format, host operating system metadata, and supported hardware architectures.

-

An OCI-compliant image can be executed and managed with OCI-compliant tools such as podman (pod manager) and Docker.

-

Images can be version-controlled giving users the suppleness to use the latest or any of the previous versions to launch their containers.

-

A single image can be used to run several containers at once.

-

Container images adhere to a standard naming convention for identification.

-

This is referred to as fully qualified image name (FQIN).

- Comprised of four components:

- (1) the storage location (registry_name)

- (2) the owner or organization name (user_name)

- (3) a unique repository name (repo_name)

- (4) an optional version (tag).

- The syntax of an FQIN is: registry_hostname/user_name/repo_name:tag.

- Comprised of four components:

-

Images are stored and maintained in public or private registries;

-

They need to be downloaded and made locally available for consumption.

-

There are several registries available on the Internet.

- registry.redhat.io (/images/images based on official Red Hat products; requires authentication),

- registry.access.redhat.com (requires no authentication)

- registry.connect.redhat.com (/images/images based on third-party products)

- hub.docker.com (Docker Hub).

-

The three Red Hat registries may be searched using the Red Hat Container Catalog at catalog.redhat.com/software/containers/search.

-

Additional registries may be added as required.

-

Private registries may also require authentication for access.

Rootful vs. Rootless Containers

-

Containers can be launched with the root user privileges (sudo or directly as the root user).

-

This gives containers full access to perform administrative functions including the ability to map privileged network ports (1024 and below).

-

Launching containers with superuser rights opens a gate to potential unauthorized access to the container host if a container is compromised due to a vulnerability or misconfiguration.

-

To secure containers and the underlying operating system, containers should be launched and interacted with as normal Linux users.

-

Such containers are referred to as rootless containers.

-

Rootless containers allow regular, unprivileged users to run containers without the ability to perform tasks that require privileged access.